- Home

- Muhammad Zafzaf

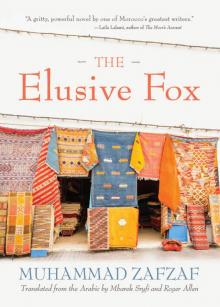

The Elusive Fox

The Elusive Fox Read online

Other titles from Middle East Literature in Translation

All Faces but Mine: The Poetry of Samih Al-Qasim

Abdulwahid Lu’lu’a, trans.

Arabs and the Art of Storytelling: A Strange Familiarity

Abdelfattah Kilito; Mbarek Sryfi and Eric Sellin, trans.

The Desert: Or, The Life and Adventures of Jubair Wali al-Mammi

Albert Memmi; Judith Roumani, trans.

Felâtun Bey and Râkım Efendi: An Ottoman Novel

Ahmet Midhat Efendi; Melih Levi and Monica M. Ringer, trans.

Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems

Ghareeb Iskander; John Glenday and Ghareeb Iskander, trans.

My Torturess

Bensalem Himmich; Roger Allen, trans.

The Perception of Meaning

Hisham Bustani; Thoraya El-Rayyes, trans.

32

Sahar Mandour; Nicole Fares, trans.

Copyright © 2016 by Syracuse University Press

Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2016

161718192021654321

Originally published in Arabic as Al-ṭha’lab alladhī yaẓhar wa-yaḳhtafī (Casa: Manshūrāt Awrāq, 1989).

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, dialogues, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-1077-9 (paperback)978-0-8156-5381-3 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zafzāf, Muḥammad author. | Sryfi, Mbarek, translator. | Allen, Roger translator.

Title: The elusive fox / Muhammad Zafzāf; translated from the Arabic by Mbarek Sryfi and Roger Allen.

Other titles: Tha’lab alladhī yaẓharu wa-yakhtafī. English

Description: First edition. | Syracuse : Syracuse University Press, 2016. | Series: Middle East literature in translation

Identifiers: LCCN 2016020131 (print) | LCCN 2016021912 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815610779 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780815653813 (e-book)

Classification: LCC PJ7876.I4 T4313 2016 (print) | LCC PJ7876.I4 (ebook) | DDC 892.7/36—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016020131

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Afterword

1

IN THE NAME OF GOD, the Merciful, the Compassionate, I will now begin by telling you the following story:

The city of Essaouira is like a woman, a woman both lock and key. I walked along its narrow alleyways, cautious and confused. Sometimes they were just wide enough for two people; at others they ended in a cul-de-sac. I checked in to the first hotel I saw and took a nap for about an hour; I had not had enough sleep the night before. A bit earlier I had been surprised by the weird behavior of a tomboyish girl; she looked like a young man but had a girl’s voice. As I was standing in front of the hotel clerk, she took a quick look at me.

“Let him share my room,” she said. “I’ve an extra bed.”

“That’s not allowed.”

“So why do you let hippies do it then?”

“You’re a Muslim woman. All the boss cares about is money. Go ahead and sleep with anyone you like, but the police poke their noses into everything.”

“I’ll be coming to your room during the night,” the girl said. “Give him a room next to mine.”

“You’re trying to get me into trouble with the boss,” the clerk said. “I’ll throw your clothes outside.”

“You think you can do that, do you? I’m a Zemouria, in case you’ve forgotten.”

The clerk fell silent and handed me the key. She walked me upstairs, and another clerk followed us. She looked around the room.

“Do you want to kill him?” she said. “There’s no glass in the window.”

“Tell the boss when he comes in the evening,” the clerk replied. “There are lots of hotels in Essaouira. Did we drag him here in chains?”

The clerk went away. She sat down beside me on the bed and took out a pack of cigarettes from between her breasts. Handing me one, she left.

I slept for about an hour. When I woke up, I was feeling nicely relaxed. Everything was calm and quiet—silent as the grave, no car engines, no human voices, completely calm. A light breeze was blowing through the broken glass. When I stood up and looked out the window, all you could see was a small yard with piles of trash and other stuff. There were closed windows as well, and the ones that were open had curtains. So nothing. Trash and windows closed, maybe closed on women. Before I came to visit the city, people told me that they—I mean women—may hide behind walls and clothes, but that in bed they do the kind of things that not even the devil’s own wife would do. Living such a double life is wonderful; in fact, human life in general is full of ambiguity. People who choose not live that way have to be stupid. An endless tragedy. Why don’t I say “comedy” instead? Human nature is both tragedy and comedy, so by definition it is ambiguous.

I could smell the fresh air coming in from the sea. The low buildings did not block my view. Outside the window the sky looked blue, clean and expansive, a welcoming sky that invites us to dissolve and hover like those tiny white clouds. So once again it is a case of everything or nothing. Sky, trash, and closed windows.

I left the window and put my head under the tap; the water was cool and refreshing. While I was drying my hair, I took out some of the money that I had put in the bag. Loosening my belt, I hid a few bills in the swimsuit pocket and put the rest in my pants.

It’s hunger! I hadn’t eaten since yesterday. When the bus stopped several times at the rest areas and passengers got off to buy meat and bread, I didn’t dare do the same. I was afraid it would be old ewe’s meat, which would give me diarrhea for two or three days. That had often happened to me before, and to other people as well. I closed the door and went downstairs. There she was, sitting in front of the clerk with her head between her hands. When she saw me, she leapt to her feet.

“Did you have a good sleep?”

As the clerk took the key from me, he kept looking at her out of the corner of his eye.

“Yes, I did sleep well,” I said. “It was totally quiet. I had some dreams too, but I don’t remember them.”

“Me, too,” she said. “I dream a lot in this hotel. It doesn’t happen to me very often.”

“Which city are you from?”

“I’m a gym teacher at a high school in Casablanca. What about you? You look like an artist. Do you paint? Act?”

“Neither. I’m a teacher.”

“Strange. You don’t look like one. Why do you keep your hair so long?”

“Oh, my hair! That’s another story. A lot of people keep their hair long. That’s not important. Do you know a place where I can get something to eat? I’m starving. I haven’t eaten anything since yesterday.”

“You look as if you don’t eat well. You’re skinny. Food’s important for the body. You must eat, especially if you’re smoking hashish. Do you smoke hashish?”

; “Yes, sometimes, but I’m not hooked.”

“Then you need to eat well.”

A few people were sitting in the hall. A man in a djellaba had chosen to sit on one of the stairs. He had hiked his djellaba up to his knees, which showed his hairy legs; his homemade pants ballooned between his thighs. He was staring vacantly all around him, from chairs to people and up to the ceiling; it was as though this were the first time he had ever been in a hotel. As we left the hotel, the girl gave the clerk a defiant look, but he paid no attention.

“What do you want to eat?” she asked. “There are lots of restaurants. Grilled sardines, sandwiches?”

“I want a plate of tripe or cow’s trotters.”

“Sure. There are lots of popular restaurants as well, but they’re a bit far.”

We made our way through a number of narrow alleys where male and female hippies were sightseeing. Some of them were sitting on the ground or by a curb, while others were standing in front of the small shops, eating sandwiches (although I have no idea what was in them).

“My name’s Fatima,” the girl said, “Fatima Hajjouj. What do you think of the name?”

“It’s wonderful.”

“But it’s just a plain old name, not like the names in TV movies and soap operas. What’s your name?”

“Ali, but I don’t think the rest is important.”

“True enough, it doesn’t matter. Names don’t have to be important, but they can distinguish, for example, between different kinds of potatoes, tomatoes, or melons. People are just like potatoes, tomatoes, and melons: we need to give them names to distinguish them from each other. Still, never mind! Here we are. These restaurants all specialize in tripe, cow and sheep trotters, and steamed heads cooked the Essaouira way. They also have their own special way of preparing tagines that are different from ours.”

It was about six in the evening. The sun was sinking in the west, but it was still bright. People did not look completely exhausted by their daily routines. The restaurants were operating alongside each other; not exactly restaurants, but big doors that opened on to three walls and a ceiling. We did the rounds first and then made our way into alleys that twisted and turned like a labyrinth. There were little apertures in the walls that revealed human beings, tagines, bread, and camel-meat kofta.

“I know these places well,” Fatima said, “They’re dirty, and they cheat you. Once I got a stomachache and had to stay in bed for a whole week; I couldn’t stop vomiting, and both top and bottom. Could be you have no idea about this type of food.”

Even so, people were wolfing it down, hippies as well, using fingernails, noses, cheeks, and hair.

“Just look at the way those people are eating,” I said. “They couldn’t care less about what you’re saying.”

“They’re immune,” she replied. “I’m not like them. If you want to eat, go ahead. No one’s stopping you. I just wanted to let you see some food that won’t make you ill.”

With that she stopped in front of another restaurant where three peasants were sitting: one was sitting in a corner eating something, his face to the wall; the other two were seated on a mat, eating from the same plate. After looking at the plate on display by the dust-covered door, she went inside.

“The owner’s a professional,” she said. “He’s good. Don’t worry about his food. He’s very clean and always washes his hands.”

We sat down on the mat. Two of the peasants eyed us warily, then went back to their food. One of them was eating by stuffing all the fingers of his right hand into his mouth; when he took them out, they made a disgusting noise.

“One plate or two?” the owner asked.

“One well done,” said Fatima.

“Make yourself at home,” he said. “You know it all. You haven’t brought any hippies here for quite a while. Are you angry with me or what?”

“No, I’m not,” Fatima replied. “Either they prefer eating other stuff, or they don’t have the money. As you well know, they spend a few days here, then leave.”

“I know. But some of them come back once or twice a year.”

The mat’s color had faded, and parts of it were threadbare. Cutlery was by the door, and next to it was a box with all sorts of stuff piled in it. Alongside it was something that looked like a coat or blanket, apparently the place where the chef slept—if not him, then someone else. When I went to wash my hands, everything was filthy. I poured out some water, then dried my hands on my pants. The towel had obviously not been washed for days; it stank, and the stains were all sorts of different colors—from black to yellow and other colors with no names.

The chef spread out a sheet of newspaper and put a plate down in front of Fatima.

“Bon appétit!” he said, wiping his hands on an apron around his waist. “It’s veal.”

I devoured the entire plateful. Fatima had just a small piece. She kept smoking and flicking the ashes off by the plate with the food I was eating and piling the butts on the newspaper. Once we had finished eating, she crumpled up the newspaper with the butts inside and put it all on the plate.

“Why don’t you visit us more often?” the chef asked her. “Come even if you don’t have any money. We’re Muslims and should help each other.”

“God willing,” replied Fatima. “I don’t like eating trotters all the time.”

“Then you can’t be hungry!” the owner replied with a laugh. “Porters have been coming here for years. They’ve had this meal for lunch and dinner. Just take a look at them, they’re as strong as mules. If you came here, you’d never have to see the doctor. They all eat here and smoke hashish a lot, but they’re still strong. Only one thing threatens them—tuberculosis. It’s kif that causes that. I smoke too, but they smoke too much.”

I handed him an American cigarette. He grabbed it eagerly and put it behind his ear. I gave him the money for the food, and we left. As we walked across a wide square, people were standing in front of piles of wheat, barley, grains, corn, and other vegetables. Some of them were shopping, while others were just enjoying the sunset and taking in the last rays of sunshine. Still others had already covered up their wares and had fallen asleep alongside them. People were heading in all directions, but only a few were buying anything.

“Morocco’s doing well,” Fatima said, pointing to the piles of grain. “Crops everywhere, and a meal costs just a dirham. Not so?”

“Definitely.”

“No one’s dying of hunger. Smuggled cigarettes and hashish are available everywhere.”

“Absolutely.”

“Life is beautiful.”

“Yes, I know.”

“Why do you always say ‘yes’?”

“Because you’re right.”

“Okay. I thought you were making fun of me.”

“I wouldn’t do that. It’s not in my nature to make fun of people. Life is beautiful, even if we had to eat on a threadbare mat a short while ago.”

“What are you saying?”

“Nothing.”

We crossed the square and went through an arch leading to the sea. I noticed women perched on a wall like storks or walking in every direction. There were very few men around. Maybe this is the way the city welcomes the evening: women near the sea and men in designated places.

As we strolled toward the sea amid this crowd of people, I felt Fatima put her arm in mine and surrendered myself to her gesture. For sure, other people in this crowd are behaving exactly the same way. So everything is possible.

2

AFTER ORDERING A CUP OF BLACK TEA, I sat down with a group of hippies on a bench. Some of them preferred to sit on the floor, while others lolled on the mat by the wall. Doors opened out on the café’s courtyard. The rooms had previously served as court offices before the building was converted into a restaurant and hotel. Some other hippies, both men and women, were looking down from the first-floor balcony. Pop music could be heard . . . it was very loud.

“Do you mind?” asked the girl next to me.

“Go ahead.”

I told her that, even though I didn’t know what she wanted. I simply agreed. This place is a world I don’t know; maybe it is different from Tangier and Marrakesh. The girl had shells in her hair and a snakeskin bracelet on her arm. She seemed totally at ease as she reached over to my cup of tea and took a sip. I had already noticed that people do that kind of thing around here even without asking permission. We took turns sipping tea. I handed the cup to another girl who was sitting on the floor a few feet away, but she declined.

“What I need’s a tonic,” she said.

She put the cup back on the table and pushed it towards me. “Are you a tourist,” she asked, “or do you live here?”

“I only got here yesterday.”

“The South’s beautiful,” she said. “We’ve visited Taroudant and Tantan; they’re both beautiful. Everything there’s authentic. We really liked going to the markets.”

The music was still blaring. Men and women kept entering and leaving, some with shoes, others barefoot. A tall young man with long hair down to his shoulders and a Cyrano-type nose came over and stood right in front of us. The girl made some space for him next to her.

“This is Maxim, my fiancé,” she said.

He did not pay us much attention but went ahead and ordered a 7-Up. Sweat was pouring off him. The man sitting next to him handed him a pipe full of kif. Cupping his hands, he started smoking and stared at the ceiling. He handed the pipe back to the same man, and he suggested that he pass it over to his fiancée. She took it from him, but, instead of taking a puff for herself, she handed it to me. I cupped my hand and did what Maxim had done. The pipe was made out of goat horn, with two strings attached, one red, the other green. I could feel the hashish I’d smoked making its way to my lungs. Handing the pipe back to the girl, I drank a sip of the tea, which was cold by now. It was black mint tea, and the mint leaves had settled in the bottom, filling almost half the cup. She handed the pipe back to her fiancé. “I don’t like smoking,” she said, looking at me. “I’ve tried, but I didn’t like it.”

“Trying’s the basic issue here. It’s addictive.”

The Elusive Fox

The Elusive Fox